The music world has its share of stars known by one name only: Prince, Cher, Madonna and Gaga. And the wine world does, too. Though not a voice or an instrument, Gaja hits high notes, carries a harmony and is melodious. Indeed, its singular name is music to the ears of collectors and connoisseurs of Italian wine.

In the 1960s, fourth-generation Piedmont winemaker Angelo Gaja began a decades-long process of modernizing his family’s Barbaresco and Barolo wines without knowing it would change the world’s perception of Italian wine.

By the 1980s, Gaja’s viticulture, winemaking, and marketing earned the status and price of First Growth Bordeaux, Grand Cru Burgundies, Napa Valley’s Opus One, Phelps Insignia and other prestigious wines. And, it blazed the trail for other Italian producers.

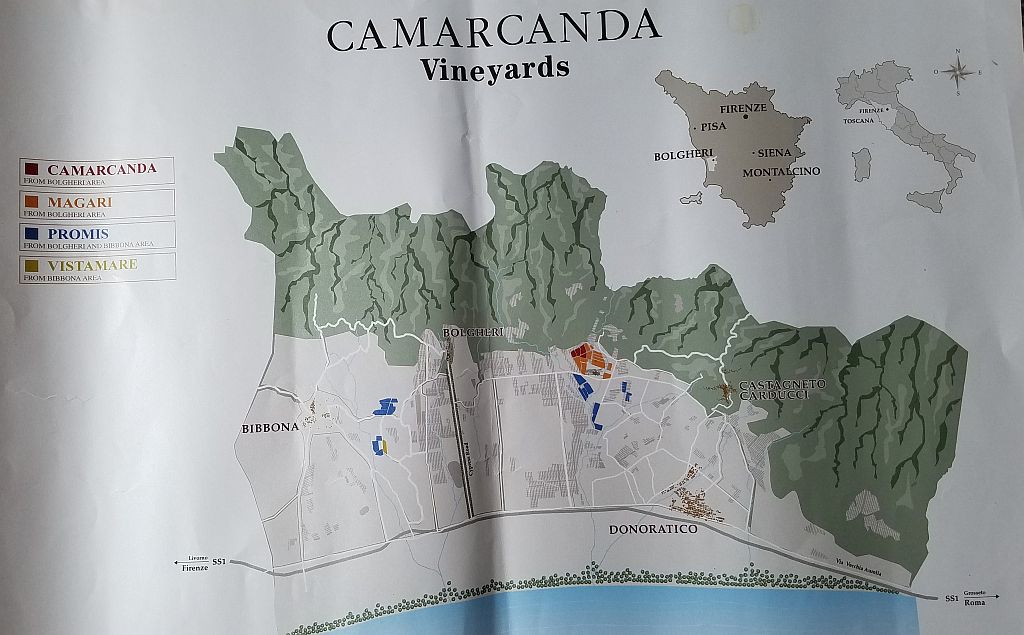

In 1994, Angelo reached outside of Piedmont and purchased Pieve di Santa Restituta, a historic winery in Brunello di Montalcino. Then, he set his sight on another region to the west—a new frontier on Tuscany’s coast called Bolgheri, one of the few areas in Italy where a vintner could establish a winery with the experimental freedoms enjoyed by New World winemakers.

After negotiations requiring no fewer than 18 trips from Piedmont to Bolgheri, Gaja purchased a farm there in 1996, naming it Ca’ Marcanda—Piedmontese dialect meaning the “house of endless negotiations.”

Unlike the other codified regions in which Angelo made wine, Bolgheri’s red wine appellation regulations (enacted only in 1994) permitted the Bordeaux varieties: cabernet sauvignon, merlot, cabernet franc (up to 100%), petit verdot (maximum 30%), and syrah and sangiovese (maximum of 50%). For Angelo, it was a canvas on which he could paint with broad brush strokes.

Unshackled by regulations and history, he planted all the varieties and divided them into three red wines: Camarcanda (50% merlot, 40% cabernet sauvignon and 10% cabernet franc), Magari (50% merlot and 25% each cabernet sauvignon and franc), and Promis (55% merlot, 35 syrah and 10% sangiovese). He also makes a white wine, Vistamare, from vermentino and viognier. In the vineyards, limestone and gravel soils add minerality to the grapes, and dark soils of ancient river beds with clay and silt, provide the moisture for ripe fruit development.

On my July visit, winemaker Giovanni Passoni presented a vertical tasting of Magari from 2004 to 2015. Magari (mah-GAH-ree), Italian for “if only it were true,” is produced from grapes grown in both soil types. Passoni said a conversion to organic farming is underway. Currently, no chemical fertilizers are being used, and natural grasses and flowers are planted between the vine rows providing natural insects to ward off infectious predators, and encouraging the vine’s roots dive deeper for nourishment.

We began with the 2004 Magari grown in a balanced season after the scorching 2003 vintage. The passage of time has mellowed and melded its vanilla-oak and black-cherry aromas and flavors. The tannins are fully integrated, giving the wine a silky texture. 90 points. Not available in the retail market.

The 2007 Magari reflects the excellence of this Tuscan vintage. A cornucopia of blackberry flavor is carried on a velvety full body with refined tannins and a long, black-fruit finish. This is a prime example of the New World-styled wine of Gaja and other Bolgheri wineries. 95 points. Not available in the retail market.

The 2009 vintage was Passoni’s first as winemaker at Ca’Marcanda. It was a very hot, and dry vintage in Bolgheri, giving the wines higher alcohol and lower tannin. By increasing the percentage of new oak barrels for aging from 60 to 75 percent, Passoni added more tannin to the 2009 Magari.

Winemaker Giovanni Passoni

Between Mother Nature and Passoni, the Magari delivers distinct blackberry jam and vanilla aromas that are surprisingly not evident in the mouth. Instead, blackberry and coffee flavors with noticeable tannins carry this wine to a balanced conclusion. 93 points. A few retailers offer this wine at $65 to $79; get a guarantee on the storage before buying.

The flip side of the 2009 vintage was the cool, wet 2010 season. “This is a favorite wine of Gaja,” said Passoni as he poured the 2010 Magari. Perhaps, it’s because the wine’s medium body carries more black-cherry with a noticeable vanilla streak, and an evident dry minerality in the finish. It’s not as New World as the earlier vintages, and might be more in tune with Gaja’s Piedmont palate. 90 points. Retail prices span a reasonable $69 to $79.

If nothing else, winemakers might think that the weatherman has a perverse sense of humor when, after a cool, wet year, they are confronted with hot, dry winds from Africa stressing their vines in August 2011. It was so intense that permission to irrigate young vines was granted by the Italian wine authorities (in western Europe irrigation is not permitted except under extreme circumstances).

The heat brought an early harvest, and a 2011 Magari with a blackberry and mildly vegetative aroma; black-plum and black-cherry flavors are front-and-center on the palate, but the vineyard’s minerality has the final word. 90 points. Widely available from $65 to $100, shop accordingly.

When another hot year surrounded the 2012 Magari, Gaja began changing the winemaking.

Passoni enlarged the barrel size to 500 liters for merlot, while keeping the traditional 225 liter (59 gallons) Bordeaux barrique for both cabernet wines. Whether it was merlot’s reduced exposure to new oak that made the black-tea scent of cabernet franc more apparent, and the calcaire/limestone taste of the vineyard more prominent, I cannot say. But both features made the blackberry-flavored wine different from the preceding vintages and appealing to me. 92 points. Retail prices range from $59 to $88.

I immediately noticed the 2013 Magari was missing its New World pungent fruit and vanilla aromas and taste, and also absent were the plush tannins and velvety texture common to many New World and Bolgheri wines.

In their place were very aromatic and flavorful blackberry and earthy accents wrapped on a medium body that was supported with tannins and acidity. This wine was definitely “a turn towards naturalness” I noted in my book before Passoni said this vintage was the first to implement organic and biodynamic techniques, including using indigenousness yeasts for fermentation. It’s a change I applaud. 95 points. A very wide price range of $54 to $90.

Pushing the envelope further, Angelo and Passoni substantially changed the 2015 Magari: They eliminated merlot; increased the cabernet franc to 60%, cabernet sauvignon to 30%, and added 10% petit verdot.

The radically changed blend put an end to the plush New World style. The new (and, for me, improved) Magari brings cabernet franc’s black-tea aroma and flavor to the fore. The cabernet sauvignon’s blackberry aroma and flavor joins its majority partner, and the petit verdot adds its blueberry accent along with acidity.

The totality is a very balance wine that is more compatible with food, and establishes a space of its own in an appellation that has a plethora of New World-styled wines. 93 points. Retail prices from $54 to $80.

As I reflected on the wines from 2004 to 2015, it was clear that two styles were sitting in front me. From 2004 through 2010, Gaja was following the majority of Bolgheri wines with its international grapes and modern style. Call it the early years of the learning curve.

But only minutes away is Sassicaia’s Bordeaux breeding (read last week’s article Sassicaia still unique). With the 2012 vintage, you can witness Gaja’s movement away from the internationalists and towards Sassicaia’s restraint and elegance. Then, in 2015, a full statement was made with organic and biodynamic farming as the new normal. With merlot banished and excessive oak barrel influence eliminated, cabernet franc and sauvignon became Magari’s identity card with petit verdot supplying acidity to offset the Tuscan sun’s ability to fully ripen grapes.

In Bolgheri’s environment, Angelo Gaja has greater freedom to position Ca’Marcanda than he did at his family’s Piedmont estate or with his Brunello winery, both ruled by regulations and history. In Bolgheri, history is only beginning, and Gaja is defining its place in it. You might say he’s marching to his own beat. And you’d be right.

Photos by John Foy & William Foy

Leave A Comment